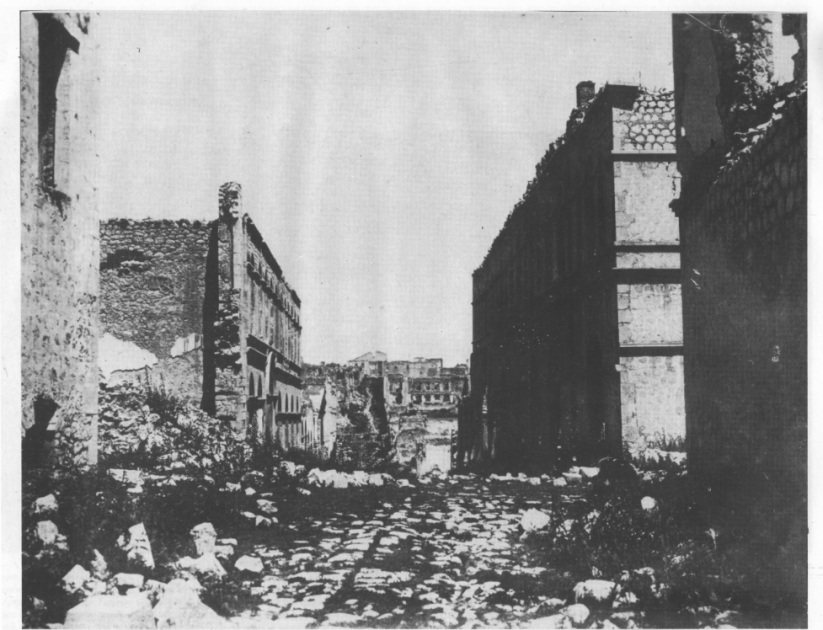

“… I was stunned by the silence. I have never felt such a terrible, artificial silence. Suddenly the silence seems to murmur, the stones whisper and move and pounce, and the hairs stand on end. In March 1920, in three days, 7,000 houses were destroyed and burned here, according to some, 3-4 thousand Armenians were slaughtered, and according to others, more than 12 thousand. The fact is that none of the 35,000 Armenians remained in Shushi. Somewhere in the stream you can still see women’s hair covered in black blood. It’s hard for a man with a good imagination to breathe here. You walk, you walk, you walk through rows of charred buildings, or rather, pieces of walls, you hurry, fearing that you will never get out of here … “

This is how Marietta Shaginyan described the city of Shushi after the massacre in March 1920. On the orders of Governor Sultanov, Azerbaijanis unexpectedly attack the Armenian district of the city during the Muslim New Year. Unable to organize a defense, the Armenians retreat in disorder, resulting in thousands of people becoming victims of an angry mob.

In early March 1920, the eighth congress of the Armenians of Karabakh rejected Sultanov’s demand to recognize Azerbaijan’s authority, announcing that they would resort to self-defense if the previously reached agreement was violated. The Azerbaijanis, seeing that they could not suppress the resolve of the Karabakh Armenians, decided to resort to arms. During March, large forces were concentrated in various regions of Karabakh, including Shushi. On March 20, Sultanov gives the Armenians three days to hand over their weapons, but their refusal causes an attack.

The Armenians tried to organize a defense, but the necessary steps were taken too late, and during the next attack, Azerbaijan did not have enough forces. In addition, the 8th Congress revealed disagreements among the Armenians, which significantly affected the organization of self-defense.

BY ORDER OF SULTANOV

Sultanov’s decision prohibits the residents of Shusha from leaving the city from March 1. All Armenian officers who could go to the regions and organize self-defense have been registered. On March 3, 7 prisoners escaped from Shushi prison, 3 of whom were Armenians. Sultanov gives three days to find the criminals. The Armenian self-defense body managed to detain some of them and hand them over to the authorities so as not to create a pretext for a surprise attack. On the same day, by order of Sultanov, officers of the Azerbaijani army were placed in a number of houses in the Armenian districts of the city. The last episode that shows that the murder of the Armenians of Shushi was a deliberate crime is the participation in it of about 150 Tatars loyal to Sultanov, summoned to Shushi from Gadzhi-Samlu on March 12. It is also important to note that along with the events in Karabakh, anti-Armenian activities are sharply increasing throughout Azerbaijan and in the Tatar settlements of the Republic of Armenia.

In March 1920, the Tatars of Boyuk-Vedi and Zangibasar rebelled again, and pogroms of Armenians began in Gandzak, Northern Artsakh and other regions.

MORNING MARCH 22

Having received a refusal to disarm, the Azerbaijani military begins to search Armenian houses in Shushi on the morning of March 22.

On the morning of March 22, on the orders of Sultanov, the military began to bypass the Armenian part (city) and search the apartments. One such guard, led by a Turkish officer, bursts into the Armenian family and demanded to hand over their weapons. In the presence of a hot Armenian young man, a Turkish officer makes an obsessive proposal to a beautiful young bride and wants to touch her. Not enduring such shame, the young man shoots the officer with a pistol. Askars kill a young man, his fiancee, his mother, his sister, and in response they shout, calling on the Turkish forces, that the Armenians are killing the Turks. They begin to break into the houses of the Armenians, and the massacre begins” (“Nor Ashkhatavor”, April 16, 1920, No. 10).

According to Arsen Mikayelyan, a member of the Karabakh self-defense body, there were about 400 Armenian servicemen in Shushi, who were supposed to provide at least partial protection of the city. He says that two police chiefs of Varanda with 90 armed men and about 160 armed residents from nearby villages were also sent to the city.

Source: Shushi Revival Foundation

“However, the city cannot use these powers. The self-defense body is not aware of the situation… Auxiliary forces act independently, and part of the population of the city, mainly supporters of Azerbaijan, led by a prominent Russophile and Turkophile Gigi Aga, begin to interfere with taking important positions and declare that & nbsp; they agreed with Sultanov that there should be no Armenian massacre,” writes Mikaelyan. (Arsen Mikaelyan, Recent Events in Karabakh, Motherland, 1923, No. 12, Boston).

THE DEFENSE WAS NOT ORGANIZED

Azerbaijanis burn the houses of Armenians, and soon the fire spreads in the Armenian region. Another participant in the Shusha tragedy, Zareh Melik-Shahnazaryan, writes that the wind blowing in the direction of the Armenian district of the city quickly spreads the fire. Some people make their way to the Karintak road in the fog, but many gather in the wide yard of Beglaryan, where Gigi Aga again declares that Sultanov will not hurt anyone.

Zareh Melik-Shahnazaryan and his five friends, after a heroic resistance, arrive at the said house, see the people gathered in the yard, and urge them to join them and retreat to Karintak.

“I knew this vile man well, and it was necessary to save the people who believed in his idle talk.”

“Near the Circassian shop, next to the bakery, we were told that a large number of refugees had gathered in one of the rich houses, but the former city manager Gigi Aga persuaded them to stay in the yard. My patience has run out. I knew this vile man well, and it was necessary to save the people who believed in his idle talk. We went to the yard… Seeing six armed fighters, Gigi Aga came up and asked what we wanted. I said: “Our commander said to release all the refugees he is waiting for on the way to Karintak. The order must be carried out.” Hearing my words, Gigi Aga took off his hat, threw it at his feet and addressed the people. “Gentlemen, do not listen to them, do not go anywhere, I will save you.”

Source: Shushi Revival Foundation

A few followers follow Zareh and his friends. Most remain in the yard, where they are killed a few hours later. Zareh’s father, engineer Samson Bek Melik-Shahnazaryan, was a member of the Karabakh military council and participated in self-defense battles. A few days before the massacre in Shushi, he was seriously wounded and died. On March 23, after hearing gunshots, 17-year-old Zare organizes a defense with his four friends. During the shootout, Aunt Zare dies, and his younger brother is in his mother’s arms. Zareh accompanies his mother and other relatives on the road to Karintak, then returns, ambushes and kills numerous members of the Azerbaijani partisans for several hours. The description of the stubborn resistance also shows that the resistance was not organized, and even the Armenians who were several houses apart from each other did not know about each other.

“When we left the courtyard of Gigi Aga, where a large crowd had gathered, the unrest in the city continued. We watched how the people of Shushi left at dusk for Karintak in a long line … The survivors left the dying “Little Armenian Paris”, as many called Shushi,” writes Zareh Melik-Shahnazaryan. (Zare Melik-Shakhnazarov, Notes of a Karabakh soldier (Memoirs of a participant in the events of 1918-20 in Nagorno-Karabakh), Moscow, 1995.)

LOATING

After the destruction of the Armenians and their expulsion from the city, looting begins. Martiros Harutyunyan, the diplomatic representative of Armenia in Azerbaijan, wrote to Khatisyan on April 16 that the Tatars themselves were telling about the events in Shushi.

“You will no longer find an Armenian in our area, and you will never meet a Turk who robbed less than a hundred thousand. There is a man who brought more than a million goods, all of them were of the same class. There is no rich or poor, everyone is equal.” (Pogroms of Armenians in the Baku and Elizavetpol provinces in 1918-1920, Yerevan, 2003).

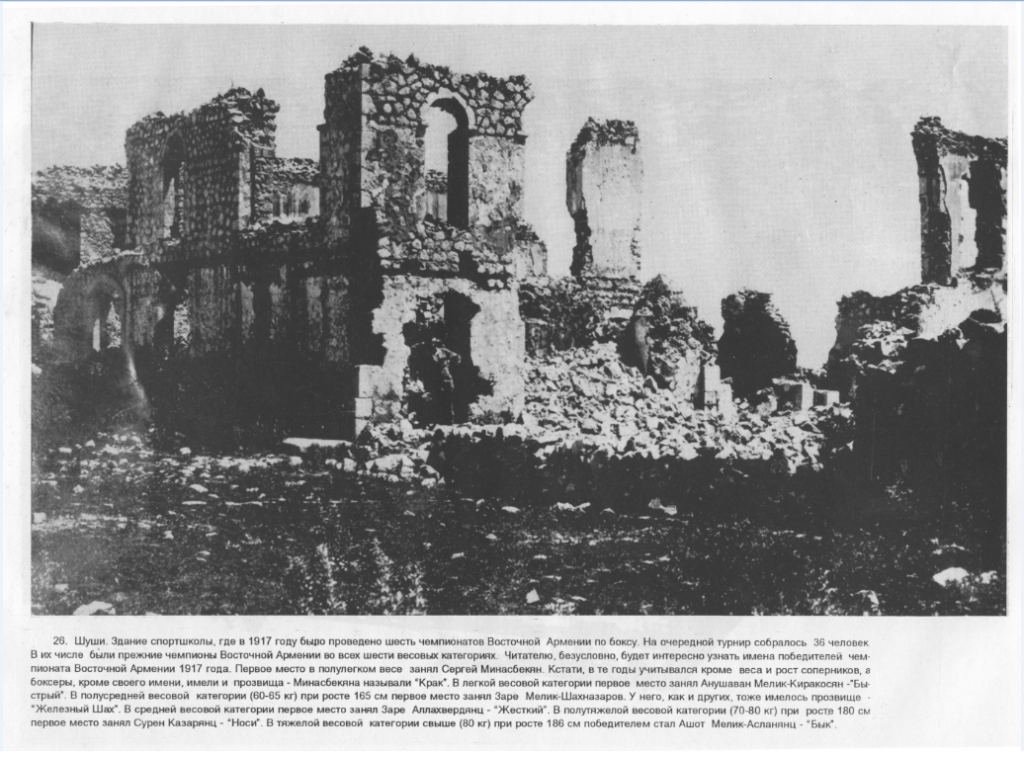

The ruins of the Armenian region of Shushi have been preserved for decades. After the establishment of the Soviet order, the Azerbaijani authorities abandoned the city to its fate. Osip Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda, wrote almost ten years after the massacre that “the city had two rows of houses without roofs, without windows, with empty rooms, rarely wallpaper, dilapidated stoves and sometimes broken furniture.”

The ruins of the Armenian region of Shushi survived until the late 1950s, when the Azerbaijani authorities removed evidence of barbarism under the pretext of building new buildings.