The web site for monitoring the cultural heritage of Artsakh monumentwatch.org writes: “Robert Mobili, who proclaimed himself the religious leader of the Udi community of Azerbaijan, demonstrated yet another illiteracy, presenting crosses and cross-compositions on the Armenian monuments of occupied Hadrut as Albanian.

It’s good that at least I realized that I limited myself to samples of the 17-19 centuries, refraining from earlier samples, otherwise it would have turned out that the entire Armenian culture of stone crosses should be declared Albanian.

It should be noted that Mobili’s deed is not his own “discovery”. Many years ago this “discovery” was made by Azerbaijani “researchers”, presenting as Albanian patterned crosses with Armenian inscriptions on the 19th century church of Nizhi.

To illiterate “inventors” who are far from Armenian culture and especially cross-stone art, therefore, not versed in the image of the cross and its compositional origin, it seemed that this type of crosses is not known in other places, and they can be safely called Albanian.

Mobili did the same, “having made a discovery” that there are similar crosses on the monuments of Hadrut. True, the Azerbaijani state false logic suggests that the Armenians should have “erased” the Albanian crosses and carved their own. It is clear that the Armenians never needed this, since these are crosses carved by their ancestors.

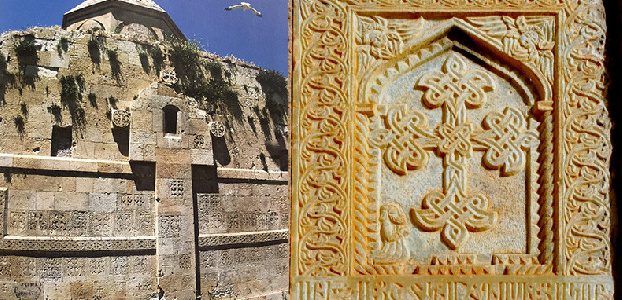

What is the declared “Albanian” cross? This is one of several dozen Armenian crosses – a multi-strand braided geometric cross, the wings of which end in lanceolate bulges.

In general, the weaving of the cross, which is a purely Armenian phenomenon, is manifested by a combination of plant and geometric motifs, which gives the cross a floral-woven appearance.

Flower-woven crosses are found in manuscripts of the 11-12 centuries (Title page, Gospel, 1181, Drazark, miniaturist Khachatur), and from the 13th century they became very popular until the 18th century.

Since the end of the 14th century, due to political and religious pressures, Armenian culture has experienced a certain decline, the art of stone crosses is gradually losing its former floral-geometric variety, crosses become flatter, motifs are more uniform and repetitive. Sculptures with crosses become completely geometric, and only a few examples retain the lanceolate tubercles of the wings of the cross, recalling the former floral-woven image.

It was a pan-Armenian process that began with the central Ashkharians (Kotayk, Vayots Dzor, Gegharkunik, Vaspurakan) and spread also in Artsakh, Utik, in isolated cases – also north of the Kur in the 19th century.

And why this process also affected the Albanian Church is clearer. Starting at least from the end of the 7th century, the Albanian Church in confessional, ritual and pictographic terms did not differ from the Armenian Church, especially since its flock mainly consisted of the Armenian population of Artsakh and Utik. Since the beginning of the 8th century, there is no separate Albanian Christian culture, no separate confession, rituals and pictography. There are only local construction, executive features that can be easily declared Albanian.

And it is clear that there cannot be Albanian crosses, unlike Armenian ones.

But let’s turn to the facts. The first examples of cross-sculptures with lanceolate tubercles exist as early as the 12th century, but they have become popular since the middle of the 14th century (for example, the cross-stones of Arinja, Bjni, Havuts Tara, Pora). This wave spreads throughout Armenia, then includes Artsakh and Utik. The political and cultural upsurge in the vast territories under the control of Persia (from Lake Van to Khachen, from Ayrarat to Ispakhan) chose this type of cross as the main one, installing them on the domes of churches under construction, on cross-stones and tombstones.

It turns out that in the central regions in the 14-15 centuries the Armenian Apostolic Church creates new forms of crosses and cross compositions, in the 16-18 centuries they spread to the territories inhabited by Armenians, so that centuries later the semi-literate Mobile and his inspirers would make “enthusiastic” discoveries and represented them as Albanian. It is difficult to imagine a more ideal example of scientific “integrity”. ”