It has been a busy month for the Cyber Security Service at Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Transport, Communication and High Technologies.

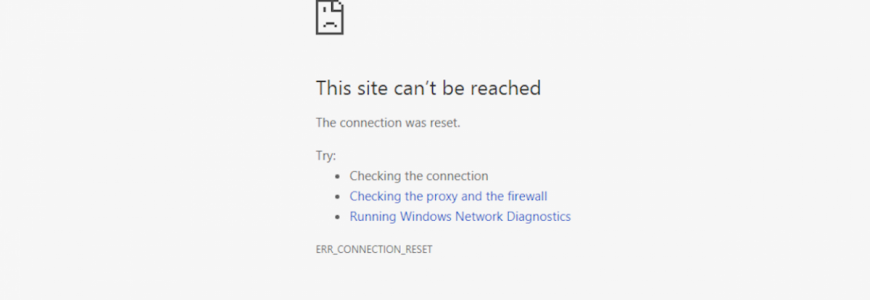

Since early August, the service has targeted a number of independent news websites – first requesting them to remove specific content, and later blocking access to these websites altogether. The blocking came after the websites featured articles on the corrupt practices of certain government officials, other stories merely reported on local grievances. Editors and journalists have been summoned to the prosecutor office for questioning over the published articles, though the editors are reluctant to comply. In their public statements, editors say there was no slander nor misinformation in any of the articles published.

Here, the Azerbaijani authorities are relying on legislative amendments passed in 2017 to the “Law on Information, Informatisation and Protection of Information”. According to these amendments, if a website contains prohibited information that poses danger to state or society (“special circumstances”), the relevant authority can block the website without a court order within eight hours of notifying the manager and editor of a website. The lack of necessity for a court order (although in regular circumstances it must be obtained) allowed the authorities to block some of the most prominent news outlets in Azerbaijan.

Since May 2017, over 20 websites have been blocked in Azerbaijan, including Azadliq Radio (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Azerbaijan Service) and its international service, Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, Azadliq Newspaper (independent of the Azadliq radio), Meydan TV, Turan TV and Azerbaijan Saadi (Azerbaijan Hour), OCCRP (Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Unit), abzas.net, obyektiv.tv and others.

When in May 2017 a court upheld the decision to block access to Azadliq Radio and others, it did so on the ground that these outlets promoted violence, hatred, extremism, violated privacy or constituted slander. This time, the decision to block access is similar, although it focuses more on slander and spreading misinformation. An editor of one of the recently blocked websites (az24saat.org) was asked to remove four articles that mentioned Ali Hasanov, an aide to President Ilham Aliyev. Monitortv.info, which was among the blocked websites, also received a note requesting the removal of articles mentioning Ali Hasanov on the grounds that these stories contained slander and lies.

There is no official data on the number of blocked websites in Azerbaijan. The Ministry of Communication, High Technologies and Transportation has so far failed to provide accurate lists. This in itself is a violation of Article 13.3.6 of the Law on Information, Informatisation and Access to Information, which requests the Ministry to prepare a list of blocked websites if it has blocked access to a resource and the court upheld this decision.

In the absence of an official resource, independent media experts such as Alasgar Mammadli argue there are far more websites currently blocked than reported – he puts the number at roughly 60. My own tests conducted during recent research at the Berkman Center for Internet Society show roughly half that number.

Keeping information away from the public

In July 2018, the Prosecutor General’s Office launched criminal investigations against four news websites: criminal.az, bastainfo.com, topxeber.az and fia.az. The former two were accused of “knowingly spreading false information,” while the latter two were accused of “spreading unfounded, sensational claims in order to confuse the public.” Criminal.az is an independent website, known for its coverage of crime-related news, while bastainfo.com is affiliated with the opposition party Musavat. The latter two are run-of-the-mill online news websites.

The decision to block these websites came in the aftermath of events in Ganja, the country’s third largest city, where three people were killed in the span of just a few days. First on 3 July, the city mayor was seriously injured in an attempted assassination, and just days later, two police officers were killed in what authorities described as riots. The authorities were quick to blame Islamic extremists for the attacks and the unrest. But independent pundits saw these claims as a means to prevent information from reaching the public.

For press freedom advocates watching the events unfold in Azerbaijan over the past two months, there are plenty of signs that the authorities are coming after what is the only remaining space for dissent in Azerbaijan, the Internet. For years now, authorities in Azerbaijan have been notorious for clamping down on press freedom, whether by jailing or intimidating journalists, shutting down publications and fining independent newspapers. And since 2013, there has also been a clear trend in curbing down on internet freedoms in Azerbaijan.

Over the years, attempts by members of the parliament “to control” social media platforms in order to avoid “external forces” from spreading misinformation on Azerbaijan have become more frequent. The most recent example includes at least 14 people being arrested for their social media posts on the grounds of making “illegal appeals”. As a result, some of these people were sentenced to administrative detention. At least three face criminal charges for allegedly “supporting terrorism” and “disrupting social and political stability”.

Originally posted here